Ireland’s current Emergency Management response reality

Storm ÉOWYN had a devastating impact throughout Ireland. It had a destructive impact on our critical national infrastructure, especially our electricity grid and water resources. Three weeks from deploying national and international repair crews, full recovery of those infrastructure resources has not been achieved. Citizens have been left traumatised by this delay in returning to full capacity. Property and community facilities lay in ruin.

This devastation is fast becoming not a one off. Widespread floods and storm damage now visit Ireland with increasing regularity. Questioning voices of the state’s strategic readiness and capacity in Emergency Management Response have become louder and louder. It is overdue “looking under the bonnet” and examining exactly how Ireland’s resilience to such a stress test would cope.

There are three legs to our Emergency Management stool; the Garda Síochána (GS), the Health Service Executive (HSE), and the Local Authorities (LAs). However, while each of these three entities are statutorily based, there is NO Superior Statutory Body overseeing their responses/outputs in the event of a civil emergency.

Legislative Advantage for an Emergency Management Structure

In the area of Civil Protection, which is a subsidiarity issue, the EU provides for co-ordination but does not legislate. It is the Member State that is required to legislate. Ireland is the only member state of the EU which does not have a legislative or statutory basis for its emergency management structure and response.

This lack of legislation puts the emergency structure and processes at a severe disadvantage in Ireland. The language used throughout the documentation in relation to Ireland’s Emergency Management speaks about ‘guidance’ and ‘recommendations’ but cannot require or compel actions. Primary responsibility rests with Member State to protect their own territory against disasters and to provide disaster-management systems. Such systems should have sufficient sovereign full spectrum Immediate On-Call (IOC) capabilities, identifiable and readily available national Notice to Move (NTM) surge capacity personnel/equipment reserves, along with additional Third-Line (3Line) national contingency resilience on notice to enable Member States to cope adequately with disasters that can reasonably be expected and prepared for.1

Evolution of Emergency Management Structures in Ireland

1 DECISION No 1313/2013/EU OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL

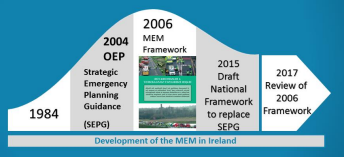

A Framework for Major Emergency Management (MEM)2 has been in place since 2006, which in turn replaced the earlier arrangements put in place in 1984. The 2006 document sets out mechanisms for co-ordination at all levels of major emergency on site, at local level, and at regional level. It does NOT cover arrangements at national level so it could be referred to as a ‘regional’ framework. The 2006 Framework is currently under internal review.

Strategic Emergency Planning Guidance (SEPG), which has specific core points, was published by the Office of Emergency Planning (OEP) in 20043 and was to be replaced by a National Framework in 2015. The National Framework is focussed on providing strategic guidance and direction to Government Departments and agencies under their aegis. This National Framework is not to be confused with the MEM Framework.

The ‘Lead Government Department (LGD)’ concept, whereby responsibility for emergency management of identified risks is allocated to the most ‘appropriate’ government Department, is at the core of the SEPG. Government Departments are not subordinate to each other. Implementing the decisions made by the LGD which may impact on another department can be complex if not unworkable. The designation of the most ‘appropriate’ government department is not always the most advantageous. In organising response, currently, care must be taken not to intrude into matters appropriate to decision-making by a Minister. In all circumstances each Department must ensure the Minister in charge of that Department is kept briefed on any emergency/crisis situation. Among core points in SEPG subsidiarity. Emergencies should be handled at the lowest possible level, higher levels of authority being kept aware of the situation, if appropriate.

Current Emergency Management Structure

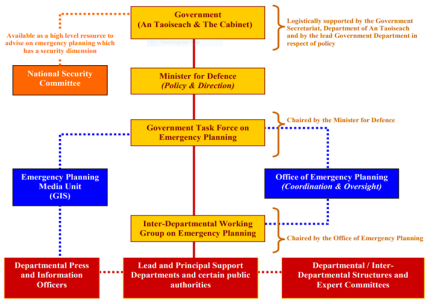

The current Emergency Management Structure in Ireland is set out in the following diagram 3.

In an emergency, a National Emergency Co-Ordination Group (NECG) is created. The primary role of the NECG is the co-ordination of a “whole of Government” response to the situation. In certain circumstances the NECG may have to act as a decision- making forum, as opposed to merely co-ordinating Departments and agencies.

2 http://mem.ie/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/A-Framework-For-Major-Emergency-Management.pdf 3Strategic Emergency Planning Guidance 2004. The Office of Emergency Planning.

This ‘decision making’ is not usual. In other jurisdictions it’s the norm. Clear policy decisions are issued. The intent of those decisions moves to specific actions at lower levels in the structure where necessary detail is addressed. An Act, like UK Civil Contingencies Act, 2004,sets out the Philosophy, Principles, Structures and Regulatory duties for Emergency Response. It’s a form of primary legislation allowing for the provision of secondary legislation to permit or require that a person or body is, or is not, to perform a duty under the relevant regulation.

Major Emergency Response – Misconceptions

Misconceptions exist about Major Emergency Response in Civil Protection, a difficult political dimension to a major emergency government to manage but it must be managed. This takes resources and political energy. Past experience from other EU countries and the US shows that the concept of a single, strong individual leader, or central organisation to “take charge” is a fallacy. However, a clear decision-making mandate and process to arrive at a decision quickly is required. The process to ensure that decisions are implemented is also required.

The various emergency services are the primary responders when disaster strikes. Secondary responders such as power and telecommunication companies, other utilities such as water and gas, the Defence Forces and Civil Defence, perform a vital role in response where the primary responders cannot provide or respond on time.

Current Gaps in Major Emergency Response

Both research and the experience in other countries shows that the following areas give the best improvement in overall response, but only achieved when demanded by regulation.

• Fostering Community Resilience, by having in-date and relevant contingency plans, providing training and creating a response structure. This needsto be the responsibility of designated officials in Resilience Fora, based on manageable and logical geographic areas.

• Co-ordination of secondary response by utilities should be on a regulatory basis. Critical Infrastructure needs to be identified and classified appropriately for action.

• An effective and truthful lessons-learned process must be put in place for exercises and response to emergencies. This will have to accommodate a no-blame functionality where appropriate. • Mandatory stress testing simulation training and exercises in benign scenarios for managers and co ordinators at senior level, to include political leaders. Desk top exercises are merely conversations. • Response actions should be in place on receipt of and in advance of a specific warning. Warning and informing the public is insufficient. There has to be specific preparatory actions depending of the degree of anticipated impact.

• Getting control of the media message is vital. This is particularly true of social media and is critical for confidence in Community Resilience.

• An ICT based decision support and reporting system will give a faster and more effective response. Currently, relevant data is significantly out of date when is it assembled for analysis. Decision makers are often dependant on media reports – key issues are not recognised.

Summary

Without a legislative basis, there is no requirement/incentive to join elements that already exist in Ireland for emergency management into an effective and efficient structure. A possible approach is to alter the role of the Office of Emergency Planning [OEP] to an Inter-Departmental legal entity with a clear mandate and appropriate authority4. This was what the government envisaged when the OEP was created in the aftermath of 9-11, in 2001. But regardless of in what government department any such statutory body would reside, it would be mere window dressing without a government commitment to annualised guaranteed funding to support such an overdue emergency management response policy. It’s what developed democracies do to safeguards its citizens.

4 https://www.emergencyplanning.ie/